‘Dying Away’: how my grandmother inadvertently inspired me

If you asked my grandmother how she was, she would invariably answer, ‘Dying away’. As far back as I can remember she talked about death and dying. When we’d visit my grandfather’s (her husband’s) grave she would tap the gravestone and wonder aloud, ‘Ah Joe, why is it taking you so long to call me?’ When I went on a trip back home to Clare with her I sat in a sugan chair (eating swiss roll and drinking cups of tea so strong ‘you could trot a mouse across them’) by the fireside and listened as she and her old schoolfriend Catherine went through an inventory of illnesses, deaths and funerals in the parish. As we left my grandmother muttered, ‘Shur, the whole world is dead’, and as they were both in their 90s much of their world really was.

My grandmother in her 97th year

On another occasion I returned home from college to find the fire lit but no one in the living room. I heard a voice summon me down the corridor: ‘Come here, I’m in the bedroom’. I wandered down to my grandmother’s bedroom to be greeted by a remarkable sight. There, on the bed, was my grandmother laid out as a corpse. She was dressed in a brown patterned dress that she’d had made for my uncle’s wedding some thirty years earlier. Threaded through her fingers were her rosary beads. ‘Take a photo’ she demanded, ‘I want to see what I look like’.

The genesis for this rather macabre incident was a conversation two nights previously where she’d outlined her plans for her funeral. This was not an unusual conversation. I got regular updates about this imagined funeral. This time she was insistent that she be laid out in this brown patterned dress. I objected, telling her that not only was it old-fashioned, but that she was now a much smaller woman than she had been 30 years earlier. ‘Yerra, it’ll be fine, shur Kirwins [the undertaker she had decided on] will sort all that out.’ Now it turned out she wasn’t entirely convinced about Kirwins’ ability to make the dress a snug fit, so a dress rehearsal took place. She concluded that I was right and the mother of the groom dress was abandoned. When my grandmother did eventually die, some some fifteen years after her dress rehearsal, she was buried in the suit she’d bought for her 90th birthday seven years previously.

‘The Dress’ as seen in 1975!

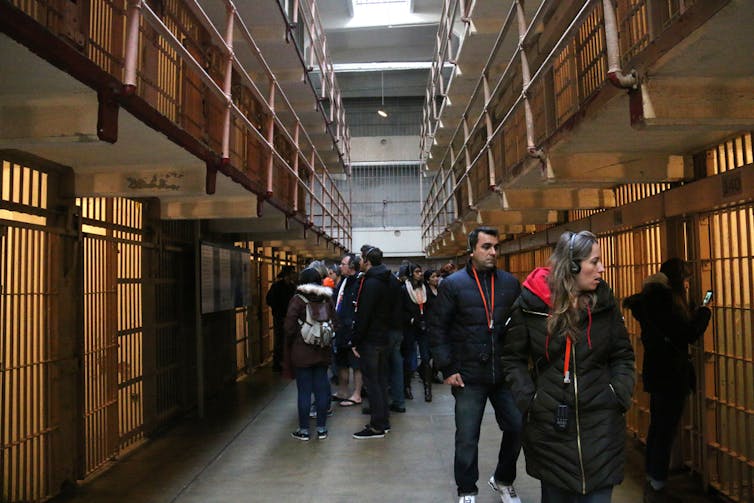

I’ve been surrounded by conversations about dying and death all my life. I’m drawn to cemeteries and memorials, to thinking about those that have gone before us and the impact they’ve had on the world. I’m sure this background has all fed into the work I do as a historian and my interest in ‘Dark Tourism’. All over the world there are museums and sites associated with death and suffering and I’ve long been fascinated by the public interest in such sites. Perhaps it is an obsession with our own mortality that causes us to seek out graveyards and tombs, perhaps in part it is pilgrimage. Visits to sites such as the concentration camps of Auschwitz and Dachau may be to better understand a horrific chapter in our past and to serve as a reminder that such things should never happen again. Visitors flock to sites of Dark Tourism – over 2 million visit Auschwitz annually, 340,000 visit Robben Island just off Cape Town while Alcatraz off the coast of California gets about 1.3 million visitors a year.

As Philip Stone has pointed out there are many shades of Dark Tourism. Some sites reflect somberly on the past, others are there to entertain more than educate (though many do both).

I find it strange that Ireland – a country that often seems obsessed with death and dying – hasn’t embraced Dark Tourism to any significant extent. There are plenty of sites that could be branded as ‘Dark’ and over the next few months I’m going on a tour of them to see how Ireland tells stories of death, famine and incarceration. For this phase of the project I’m focusing on site-specific locations – places that are associated with the stories they tell. I’ll be visiting prisons, graveyards, ships and workhouses. At the moment I’ve twenty sites on my list, but I’m sure there are many more scattered around the country. I’m interested in any and all suggestions of places that I should visit on my travels so please leave a comment or email me at g.p.obrien@ljmu.ac.uk if you have any sites to add to my list.